|

A song about natural selection by

cognitive psychologist Tania Lombrozo |

Happy Darwin Day! Today I’m running a bunch of activities at Seattle’s Darwin Day celebration, noon to 3 in Bellevue. To coordinate with the organizer, I made a list of evolution activities that I’m ready to run, and here it is. I’ve done most of these activities at school visits or other events, but a few are untried.

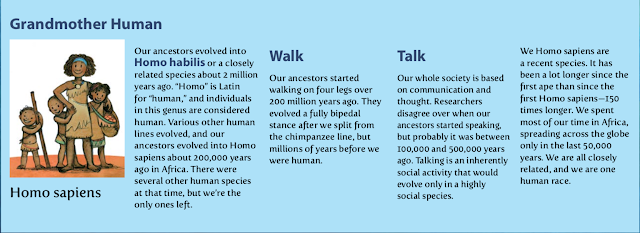

Grandmother Fish

The book is a starting point for discussions about evolution and about the history of life on earth.

Wiggle-Along: A read-along of the book, with five kids in front demonstrating the sounds and motions of each Grandmother. Everyone follows along. Great for kids getting their wiggles out. If you’re not familiar with the book, you can see an early draft being read to kids for the first time in

this video, which we originally did for the Kickstarter campaign in 2014.

Timeline exercises: The five kid volunteers are part of a visual demonstration of how much time has passed since each of the Grandmothers, compared to each other, compared to Earth’s history, and compared to the existence of the universe. You can print full-size images for the five “grandmothers” to hold,

available here.

The story of my book: For kids who dream about being authors someday, the story of how I wrote Grandmother Fish is partly inspirational and partly a caution. It took me many years to figure out how to do the book, and I needed help from many friends to get it right. You can do great things, but it can take a long time, and you need to learn to accept help.

Q&A: There’s a ton of science behind Grandmother Fish that is not obvious on the surface, so if kids have questions, I have answers.

Clades, the Evolutionary Card Game

This is my animal-matching card game of evolutionary relationships. A “clade” is a complete branch of the evolutionary family tree. For example, “birds” composed a clade, and reptiles and birds together form a larger clade called Sauropsida. Up to 8 kids can play at once, but they’d have to all squeeze around a shared play area. This game is suited to an activity center, sort of like a craft session but for a game instead of a craft. People can drop into and out of games. The game is also a “conversation starter” for evolutionary history, as represented by the animals on the cards. Clades is illustrated by Karen Lewis, the same wonderful children’s artist who illustrated Grandmother Fish.

Kids’ Songs and Dances

We humans all evolved from people who sang and danced around the campfire all night. This stuff is fun for kids, and when kids dance, it’s an excuse for grownups to have fun, too.

“Charles Darwin” dance: The hokey-pokey meets evolution, where kids evolve from fish into humans one body part at a time. Here a

link to the lyrics. They start like this, and you get the idea.

“You put your right fin in,

You take your right fin out,

You put your right fin in,

And derive an arm right out…”

“If You’re Disgusted and You Know It”: A lot like “If You’re Happy and You Know It” but with universal facial expressions and sounds for key emotions: happy (smiling), sad (weeping), scared (scared face), disgusted (yuck face), and surprised (“oh” face).

“Five Violet Spiders”: A familiar tune gets original lyrics and a video by cognitive psychologist Tania Lombrozo. The song demonstrates natural selection, as the most visible spiders get eaten.

Stand Up Interactive Activities

These activities require people to stand up and move around.

Bloodlines: Roll giant dice to simulate the identification of Mitochondrial Eve and Y-Chromosome Adam in deep time. Little kids can do it, although it involves probably going extinct.

Mates: Mate-choosing simulations with cards. We simulate monogamy, mixed polygamy, and total polygamy. Kids can do it, but that might be weird.

Life-on-Earth Timeline: This activity follows the Grandmother Fish reading. It could also be cut loose as its own activity.

Walk-and-Talk

Stand and be counted with your people! Everyone stands in a group. The leader presents the group with either/or choices such as, “If your favorite dinosaur is a Triceratops or other herbivorer, move left. If your favorite dinosaur is a Tyrannosaur or other predator, move right.” Everybody moves and then gets to see how everyone else in the group answers each question. Opinionated people on either side can explain their choices. Periodically we stop and discuss, and then move on to new questions. The questions cover evolution questions that people can answer personally, such as favorite extinct animal, experience with evolution while growing up or in school, mammals versus birds, personal experiences (hunting, foraging, cooking, having children). It’s something of a mixer.

Kahoot! Quizzes

These are two short online quizzes with my original questions and creative-commons images. They cover big ideas, not trivia. For each question, one option is a silly answer, so kids who can’t actually answer the questions can still play along by spotting the silly answers. I use each question as a way to put some aspect of evolution into a greater context, showing how this information fits into the larger picture. These quizzes are on the Kahoot! site, which allows people to answer questions on their phones and participate in the quiz all at once. The quizzes are free for the public to use.

Wings Quiz: 12 questions on wings, which was the theme of Seattle’s Darwin Day this year. You can also listen to a 15-minute audio of my practicing running the quiz. You can see how I pull in evolutionary concepts and use the questions as starting points.

Evolution Quiz: 10 questions on evolution, Charles Darwin, and life on Earth. These are big ideas, like what Darwin thought of “savages”, not trivia, like what years Origin of Species was published.

Poetry Reading: “The Sea” by Mary Oliver

This poem is about a woman yearning to return to the fishy life of her ancestors. It’s so good I memorized it to recite at Burning Man one year. Evolution isn’t just about what happened in the past. It’s also about how we feel today, knowing that we are connected to all living things.

There’s only time for me to do a fraction of these activities at Darwin Day today, but I hope to do the rest someday.